It is no secret that food-insecure households in South Africa are finding it increasingly difficult to include animal protein in their daily diets, not least because of the COVID-19 pandemic and rising food prices.

From approximately 2005/06, broiler chickens began beating marine-capture fish to become the cheapest animal protein source in the country (tinned pilchards are excluded from this comparison). This is despite the 50% to 100% price spread between the large-scale producer costs at the base of the broiler chicken value chain and supermarket retail prices for frozen dressed birds hovering between R45/g and R55/kg.

At the same time, there appears to be opportunities for small- and medium-scale broiler producers, despite higher feed, abattoir and other input costs, to retail directly to consumers, bypassing the formal value chain.

Using the small-scale producer cost model, Thapi AquaKulcha (Thapi) has estimated the ex-abattoir cost of broiler birds to be between R29/ kg and R31/ kg live birds. For comparison, Thapi used a figure of R30,22/ kg after added abattoir costs, converted to an edible meat yield of 46,1%.

Beef, lamb and pork cannot compete with the price of broiler chickens. These animal

protein sources were therefore excluded from the most appropriate cost comparison to establish the food-security value proposition of the various animal protein sources brought to an edible meat yield basis. Comparisons were therefore made between broilers, hake, pilchards and marine tilapia.

It was found that a large-scale marine tilapia industry could provide consumers in the rural Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal with affordable fish at R37,76/kg edible meat yield. That’s around half the cost of Cape hake (R75,18/kg), less than two-thirds of the cost of tinned pilchards (R65,08/kg) and less than two-thirds of the cost of broiler chickens (R65,56/ kg), all on an edible-meat-yield pricing basis. Using this comparison, marine tilapia thus offers unrivalled food-security potential.

Freshwater tilapia aquaculture

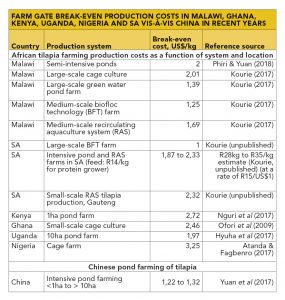

The current freshwater tilapia farming production philosophy, which is based upon the use of intensive pond farming, a recirculating aquaculture system (RAS) and complete extruded aquatic feeds at a cost of R14/kg for a 28% to 32% protein grower ration, puts the farm gate break-even production cost at R28/kg (best case) and R35/kg (worst case).

This is uncompetitive against large-scale broiler producer costs, which are between R21/kg and R23/kg at the base of the value chain, according to the South African Poultry Association. Chicken is also the preferred meat choice nationally.

Clearly, when the farm gate break-even producer costs of farmed tilapia on a live-weight basis are well above R20/kg, this food source offers little merit as an affordable alternative meat protein for food-insecure households in South Africa.

The major cost drivers and challenges confronting South Africa’s fledgling tilapia farming sector are:

- High feed cost at more than R14/kg for 28% to 32% protein grower rations;

- Suboptimal water temperatures for most of the year due to the poor location

of tilapia farms more than 500m above sea level and outside the warmer east coast and low-elevation inland sites; - The use of inappropriate production technology for low-cost and scalable production for intensive pond farming and RAS;

- Lack of economies of scale and scope.

In contrast, large-scale farmed production of Mozambique tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus) in seawater, using biofloc technology (BFT) and applying 2021 costs and pricing, clearly represents, potentially, the cheapest animal-meat protein source in South Africa.

Comparing feed-use efficiency

How do BFT, RAS and cage- and intensive pond-grown tilapia compare with broiler chicken production metrics, in terms of feed-use, nutrient recovery efficiency and feed cost per unit of edible meat yield (calculated at R15/US$1)?

The table shows the efficiency of feed-use in BFT tilapia aquaculture compared with intensive pond farming and the use of an RAS in tilapia aquaculture as opposed to broiler chicken farming. As can be seen, BFT tilapia production competes favourably with broiler chicken farming in terms of feed-use efficiency, on both a live-weight and edible-meat yield basis.

In contrast, neither tilapia culture when using intensive ponds achieving an average of 7ha/year not RAS tilapia production technology can compete in terms of feed-use efficiency against broiler chicken farming, given current pricing of standard extruded tilapia grower feeds at a cost of R14/kg ex-factory in South Africa.

The problems of a suboptimal local climate for productive and efficient tilapia culture, high feed costs (extruded feed for tilapia costs of around R14/kg for a 28% to 32% grower ration), and lack of economies of scale all call for a more determined, targeted and sophisticated response.

Thapi envisages large-scale, professionally managed, majority worker-co-owned intensification of the tilapia farming sector, emulating certain elements of the highly successful broiler farming model and adapted for local suboptimal climatic conditions and the use of BFT, as key to the success of an efficient tilapia culture sector in South Africa.

More specifically, Thapi’s vision for 2035 is production of 20 000t tilapia per cluster, offering the lowest-cost animal protein source in South Africa at a farm gate break-even price as low as R15/ kg live weight at the base of the value chain.

This would be due to the benefits of specialisation and the economies of scale and

scope, and is based on long-run costs at today’s input prices before onward sales to a processing plant.

In sum, a large-scale BFT-based marine tilapia industry on the east coast of South Africa

would be the least-cost producer of tilapia in the country, the least-cost source of animal protein in the country, and the least-cost producer of scalable quantities of tilapia in Africa.

Equally, the product would be highly competitive internationally, with farm gate

break-even production costs of around US$1kg live weight (see table).

This is 18,4% to 25% lower than break-even production costs of between US$1,22/ kg and US$1,32/ kg (R18,30/ kg and R19,80/ kg) in China, based on Chinese research.

Positive pull

Because of its proposed size, Thapi AquaKulcha’s project could create an equally significant demand for feedstock raw materials. This could see between 15 000 and 30 000 farming families per cluster in rural Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal (based on 20 000t of tilapia) receiving the opportunity to enjoy food security and generate an income.

Thapi anticipates five clusters, of up to 150 000 farmer families and 100 000t, of fish production on the Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal coastline. The project calls for farmers to plant feedstock crops for the marine tilapia industry and also produce nutritious crops, such as pulses and legumes, maize and sorghum for local/regional consumption and other markets.

The project is designed to rescale developmental objectives, using new growth conduits to address the challenges of rural poverty, unemployment and inequality on the one hand, and rural nutritional security and food sovereignty on the other.

Thapi’s vision aims to address the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal No. 2 of ending hunger, achieving food security and improving nutrition, while promoting sustainable agriculture and aquaculture. At the same time, the project would indirectly and directly support the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal No. 14, which targets healthy oceans for food security, nutrition and resilient communities.

A counter to local unemployment

The advantages of the proposed Thapi AquaKulcha project and its potential to mitigate household insecurity should be viewed against the backdrop of the socio-economic conditions in rural Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal.

In these two regions, respectively, nearly 60,6% and 50% of households were dependent on social grants in 2019 and the official unemployment rate was 47,9% and 29,6% over the period October-December 2020, according to Statistics South Africa.

Email Ramon Kourie at ramonk@thapiaquakulcha.co.za.